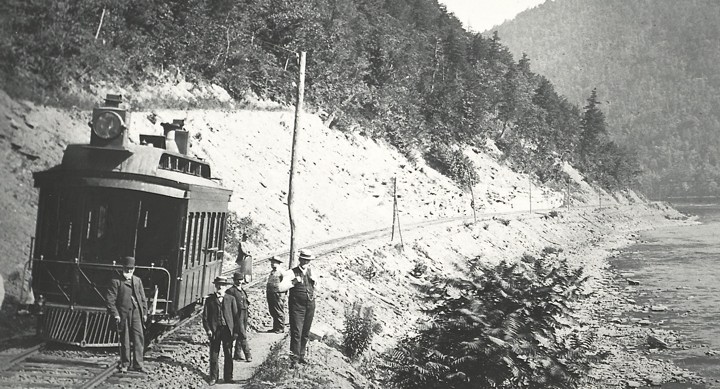

A working party on the Fall Brook Railway with the pony engine "John."

Supt. G. R Brown is pictured at left, on the track, with a cane.

Photo courtesy Sornberger Photo Collection, New York State Library

General Superintendent G. R. Brown

and the "Brown System of Discipline"

George Ransom Brown was born near Elmira, NY, September 9, 1840, the son of Stephen T. and Rebecca Jane (Moore) Brown. At seventeen he was a teacher in the district schools. As a youth he was a waterboy during the construction of the Northern Central Railroad into Elmira. Later he found employment as a telegraph lineman, and later was placed in charge of the work. In 1864, he took charge of the maintenance of the newly constructed telegraph line of the Fall Brook Company, with headquarters at Corning, NY. He learned the Morse Code and became a train dispatcher. In 1867 he was appointed Train Dispatcher and Superintendent of the Tioga Telegraph. In 1882, he was appointed assistant superintendent of the railway; became its general superintendent in 1886, following the death of Alonzo Gorton, which position he held until until the road was turned over to the New York Central system in 1899. ** He died in 1916 in Rochester, at the age of 76.

His love of railroading and his solid control of the Fall Brook affected railroading

across the country.

He became nationally acclaimed for his work on the Fall Brook. He is best known for his discipline

system of "Brownie Points" - a common term today, and has been credited as being the first railroad superintendent to prohibit drinking by employees.

He became nationally acclaimed for his work on the Fall Brook. He is best known for his discipline

system of "Brownie Points" - a common term today, and has been credited as being the first railroad superintendent to prohibit drinking by employees.

He did not automatically

suspend men for accidents as was the common disciplinary practice. Instead, beginning in 1885, Brown wrote that accidents and "close shaves" both convey safety information. According to the severity

of the event, he gave demerits, or negative points. Merits, positive points, were awarded for good service. However, too many negative points could result in dismissal. An employee's record of points was

privately held, a matter between the employee and the Company. Brown would issue "bulletins" as a way of communicating what was learned from acts, both positive and negative. An annual bonus was paid

to conductors with perfect records with no negative points.

The Brown system, corrective rather than punitive, was adopted widely by railroads, and acknowledged as a fairer way to treat employees

than automatic firing. At a meeting in 1897 of the American Association of Railroad Superintendents, the officers discussed with appreciation "Brown's Discipline" (Railroad Gazette 29,

1897:690-691). At the meeting, the assembled superintendents concluded regarding the safety bulletins, "The usefulness of the bulletins is as self-evident as that of records."

From the Journal of Railroad and Locomotive Engineering, 1896:

The Fall Brook Railroad is 250 miles long and handles the heaviest tonnage, for the same number of miles, of any single track road in America. Last year it carried 488,000 passengers - it has never killed a passenger - and injured two of them; they were both drunk at the time. It ran 21,167 trains of freight, containing 670,000 cars, mostly coal laden. Three employees were killed and 47 injured. This is the road where there is no lay-off for punishment - results seem to prove the rule a good one.

In the 1896 Volume of Locomotive Engineering, G. R. Brown describes his merit system in an article "Discipline Without Suspension". In addition, this article gives a wonderful view of daily operations on the Fall Brook System, and the challenges faced by the General Superintendent.

And Engineer James N. Robinson, of Corning, NY, describes "An Engineer's Experience with the Brown System of Discipline" in a later issue of Locomotive Engineering that year. Told from the employee's point-of-view, Mr. Robinson shows the devotion that early railroad employees had to their work.

He wrote definitively of his system in "The Discipline and Education of Railway Employees" by G. R. Brown - American Engineer and Railroad Journal, Volume 73, February 1899

Locomotive Engineering, June 1899, describes Mr. Brown's retirement:

Mr. G.R. Brown has retired from the position of general superintendent of the Fall Brook Railway, on account of the absorption of that road by New York Central. Mr. Brown entered the service of the Fall Brook Railway in 1864 as a telegraph operator, and has been with the road ever since. He was successively train-dispatcher, superintendent and then general superintendent. When he became general superintendent the company had been suffering from numerous accidents and wrecks due to recklessness and carelessness. Mr. Brown instituted a rigid system of discipline by means of bulletin board notices and the keeping of records of the men, but no suspensions were made. The plan worked out so well that accidents almost ceased within a few months ... Many railroad companies have now adopted the Brown system in full or modified form.

When the New York Central took over the Fall Brook Railway in 1899, all officials of the latter company were replaced and Mr. Brown went to the New York & Pennsylvania Railway at Canisteo as General Manager. He died November 4, 1916 in a hospital in Rochester, N. Y.

In an article in the Westfield, PA newspaper on 2/7/1901, Mr. Brown's distaste for the NYC takeover of the Fall Brook Routes was on full display:

"I have no desire of returning to the Fall Brook under Central management in its demoralized condition, with its disasterous wrecks, delayed trains and dissatisfied employees, and attempt to restore order out of chaos.

"The Fall Brook last year moved about 8,169,544 tons of freight in a single track with trains about on time. The train force averaged but eight hours and forty-one minutes for a day's work and the overtime paid the entire force for a full year was but $226.03 and for three previous years it did not reach $400 per year.

"To restore these results the sentiments of the employees must be changed. In other words their heads, hearts, habits and discipline must be corrected to be in full accord with the company and not until then will good service follow.

"To have good locomotives, cars and tracks with modern appliances, is desirable, but to have competent, loyal employees is absolutely necessary to insure successful and economical operation. The men are discouraged, and are doing the work as they feel, and that is not very well.

"If the Fall Brook did a certain thing a certain way the New York Central are sure to do it just the opposite and the two methods speak for themselves in unmistakeable language.

"There is no reason why 12,000,000 tons per year cannot be carried over the Fall Brook without unusual delay. The heads of the transportation departments want double tracking and not the road. They have been side tracking some of their heads and everyone hopes to see an improvement in the future.

"The methods that produce these results have been relegated to the scrap heap, as not worthy of practice. It is amusing to note the wonderful strides they are making with their double and four track ideas, practiced on a single track road, and while inspecting the ruins it is indeed a pleasure to know that more than half of the railroad mileage in the United States is practicing methods originating on the Fall Brook and not one of these roads has abandoned them except the New York Central on the Fall Brook, and this to the deteriment of the lessees, employees and public generally. Mr. Vanderbilt was attributed as saying "The public be damned," and he seems to be preaching from this text on the Pennsylvania Division".

In the Railway Review he wrote:

"The first thing to be done to increase the carrying capacity of single-track roads is to double-track the heads of the transportation departments instead of the roads. Get the standard gauge man as the head of all departments, and hold him responsible for results. No road or division of a road (single-track or otherwise) can be successfully managed with the heads of different departments working against each other. One man must be in absolute control and located where the work is being done. The general offices hundreds of miles away cannot manage the details of a division."

Bertrande H. Snell, of Parish, Oswego County, N.Y., was a telegrapher all his working life and wrote a series of articles for the Syracuse Post-Standard. In one, he recalls meeting G. R. Brown:

Superintendent Brown was a short, stocky man, full of years and not entirely empty of cheer.

"You will understand, gentlemen," he orated as the refilled glasses were set before us, "that I am unalterably opposed to liquor in any form, shape or substance. I have dedicated no small portion of my life to aiding in its utter end and complete annihilation, and I am never averse to asking of volunteer aid in getting rid of it - barkeep, set up another round!

"Right at this point, I became possessed of an unfortunate urge to be smart. I was well aware of the fact that Mr. Brown was the author and compiler of the standard railroad Rules which was then - as now - in general use on American railroads; and, as he continued, I recalled one of the most controversial and widely quoted paragraphs in his famous volume.

"But," I butted, "what about your Rule G, Mr. Brown?"

(For the benefit of the uninitiated, I here quote that famous rule: "Employees will not use intoxicating liquors as a beverage and will not frequent places where such beverages are sold.")

Mr. Brown placed an elbow on the bar and slowly turned to face me. His expression at the moment indicated that he sorrowed more than angered, and he prodded my Ascot tie with a stubby and forcible forefinger as he replied:

"Son, a remark like that indicates not only that you have a lot to learn, but likewise that never in God's world will ye learn it! A man who's smart enough to write a book of rules that's now in use on every streak o' rust in the country ought to know how to get around any or all of them same rules himself.

"Now, my festive brass-pounder, you pick up that o' yarn that you just throwed onto the bar and you make tracks through that outside door before I lose my temper and buy you another drink - and that, my sprightly caboose lawyer, is somethin' I know dang well you couldn't stand, nohow!"

(Thanks to Richard Palmer for providing this)

George R. Brown, Who Did Much to

Build Up the Fall Brook Railroad,

Passes Away at His Home.

George R. Brown, a resident of Euclid Avenue, died very unexpectedly at Rochester, Saturday night, after an extended illness. Mr. Brown was a former resident of Corning and had resided in this city about 15 years. He is survived by his widow in this city, and a daughter, Mrs. Dean C. Balcom of Corning. The remains have been removed to this city and the funeral will be held at the family home Tuesday at 1 p.m., the Rev. A. E. Legg of Hedding Church to officiate. Burial will be in the cemetery in Corning.

In his early life, Mr. Brown was a civil engineer and was engaged in railroad construction. About 30 years ago, when the Fall Brook Railroad was in a run down condition, Mr. Brown was selected by the late Sen. George Magee, the principal owner of the road, to act as the general superintendent. Mr. Brown saw so many cases of intemperance among the railroad employees that he promoted the rule that forbade men on the Fall Brook to drink. It was called "Rule G" by the road, happening to come into that place alphabetically, and has since been called by the same name by all the roads which have adopted it. Mr. Brown held fast to his rules of discipline, while General Superintendent of the Fall Brook here for a period of twenty years, and the famous rules he inaugurated are now use on practically all the railroads in the country.

When the Fall Brook was absorbed by the New York Central, Mr. Brown became general manager of the New York and Pennsylvania line, with headquarters at Canisteo. After over half a century of railroading, he retired fifteen years ago, and has since then resided in retired life at his home on Euclide avenue and West 4th street.

He was always proud of his record as a railroad superintendent and particularly in the fact that while his rules were first pronounced “sure ruin,” he raised the Fall Brook railroad from what he promised to be a decided failure to a prosperous company and the employees became most reliable. Several years ago the Fall Brook road was purchased by the New York Central Railroad Company and is now known as the Pennsylvania division of that great system. (Elmira Star-Gazette - November 6, 1916. )

(Again, thanks to Richard Palmer for providing this)

** from National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol 17 J. T. White, 1921

Early coal trestles at Salt Point, Watkins, NY

Photo: Schuyler County Historical Society

G. R. Brown Residence, Corning, NY

From an 1882 Map of Corning